Every 11th November Pinewood Studios hosts a Remembrance Service, not only in memory of the fallen in every conflict – but specifically to honour of the members of the Army Film & Photographic Unit (AFPU) which also embraces the RAF Film Production Unit (RAFFPU). This year the service was conducted by the Reverend Nick Todd CF, Chaplain to the Irish Guards and the two minutes silence at 11 o’clock was marked by Colour Sergeant Shaun Held, Senior Bugle Major, The Rifles – with the Colours presented by the Royal British Legion, Iver Heath.

Every 11th November Pinewood Studios hosts a Remembrance Service, not only in memory of the fallen in every conflict – but specifically to honour of the members of the Army Film & Photographic Unit (AFPU) which also embraces the RAF Film Production Unit (RAFFPU). This year the service was conducted by the Reverend Nick Todd CF, Chaplain to the Irish Guards and the two minutes silence at 11 o’clock was marked by Colour Sergeant Shaun Held, Senior Bugle Major, The Rifles – with the Colours presented by the Royal British Legion, Iver Heath.

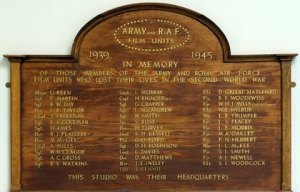

Formed during WWII, the AFPU and RAFFPU had their headquarters in Pinewood Studios where a permanent reminder in the form of a Memorial Plaque, which records losses proportionately as high as any Unit in the war, is displayed in the corridor leading to the cutting rooms where so much of the film footage, which is still frequently seen on television, was edited.

Paul Clark is the person who is currently looking after the AFPU Veterans Association, and organises the attendance of the remaining members and the friends and families of those who are no longer with us – as well as the reunions over the years (which were inspired originally by Captain Alan del Strother, a one-time Adjutant at Pinewood). He took over the reins from Harry Thompson, who in turn had taken over from George Reeves. Because PR and war correspondents were attendees at the reunions they are also listed on the roll of honour – and let us not forget the darkroom technicians, camera mechanics, clerical and transport staff who all played a vital part in running the Unit and are deserving of equal listing. As Paul mentioned in his introduction at the service, the membership is reducing each year but I think that he can rest assured that this wonderful piece of history will continue to be honoured by Pinewood Studios and the friends and families of the AFPU and RAFFPU members.

History

Before the start of the Second World War the Central Office of Information controlled publicity related to all military and civil actions with the Director of Public Relations in the War Office being responsible for the affairs of the British Armed Forces. When the War broke out in September 1939, just one Army photographer, Geoffrey Keating and one film cameraman, Harry Rignold, accompanied the British Expeditionary Force to France.

It was quickly realised that the front line would be a dangerous place for untrained photographers as well as the possibility of them endangering not only themselves but the people in the battles they would have to photograph. On 24th October 1941, the Army agreed to form a corps of trained photographers and cameramen. The unit was called the Army Film and Photographic Unit (AFPU) and, under the leadership of Lt. Colonel Hugh St. Claire Stewart, Pinewood Studios was selected as their headquarters – as well as the RAF Film Unit and the Crown Film Unit, who produced propaganda films for the Ministry of Information.

There were many professional film and press photographers who had already been called up for service so they were quickly located and brought together in Pinewood Studios, which served both as a headquarters and training centre for the Units. Number 1 Unit was based in Cairo, which was to come into its own when retreat changed to offensive at Alamein, opening with the launching of the barrage skilfully and uniquely filmed by Sgt Billy Jordan, MM – who continued as a cinematographer, working in news, features and shorts for Associated-British Pathé, Alfred Hitchcock and The Children’s Film Foundation.

On D-Day, 6th June 1944, ten men from the newly-formed AFPU went with the first wave of troops ashore, whilst others landed with the airborne troops – continuing to accompany the Armed Forces as they fought through Europe.

Two experienced pressmen, Ted Malindine and Len Puttnam were among the photographers called up to record the British Expeditionary force in 1939 & 1940.

They both recorded the Dunkirk evacuation and were themselves evacuated twice from the French beaches.

The AFPU was deployed in all theatres of Allied action, often alongside special forces such as the Commandos, the Chindits, the Airborne, the SAS, the Special Boat Squadron and the Long Range Desert Group. All the major campaigns were filmed and photographed – and the footage from the Desert and North Africa Campaigns was used to produce ‘Desert Victory’ which won an Oscar for the best war documentary. In later years footage from D-Day provided background information for the opening scenes of ‘Saving Private Ryan’.

The Italian campaign and Western Europe embraced the action at Monte Casino, Arnhem, the Rhine Crossing and the relief of the Belsen Concentration Camp. The Far East campaign was covered by Number 9 Unit under the umbrella of Admiral Louis Mountbatten and footage was used to produce ‘Burma Victory’.

As an example of the breadth of work of the members of the AFPU, the following passage is part of the memories of photographer Frank Covey:

… ‘Having returned from North Africa and completed my parachute training in January 1944, we were waiting for assignment to units. There I saw a notice which read … “Volunteers needed for a course on Photography” … when we got to Pinewood we were met by a gentleman in civvies, who introduced himself as Major David MacDonald, our new CO. We were told that all regular army bullshit was out and that there would be no time for parades or suchlike – but that we should keep ourselves correctly dressed, behave and put all our efforts into the task ahead.

The commanding staff were all well known people from the film industry. The Boulting brothers with Richard Glendinning and David MacDonald formed the nucleus. There was also the Crown Film Unit at Pinewood making war films such as ‘Target Tonight’, ‘Western Approaches’ and ‘Journey Together’ with Edward G Robinson. A young actor starred in some of these films, who we got to know as Dickie Attenborough! All in all we were a mixed bunch of film, newspaper and magazine photographers from across the country …

… ‘We broke out of Normandy and followed the German retreat, at times entering villages in forests and finding that we were the first British troops they had seen. We joined the Guards Armoured Division for their dash to Brussels. With the infantry (Welsh Guards) led by armoured cars of the Household Cavalry and Cromwell tanks – we dashed 100 miles and got to the city in the late afternoon of 3rd September 1944. It was crazy, we were covered with flowers, given bottles of Brandy etc …

… ‘We went to the concentration camps of Bergen-Belsen and Neugamme near Hamburg, where we saw the terrible carnage. At Neugamme the ovens were still there and all over the camp white discs were scattered on the ground, which we discovered later were the compressed ashes of those burned’ …

After the War

Many of the former members of the AFPU became established in the film and photographic industries after the war and several became exceptional figures in their chosen professions – here are three examples:

John Aldred joined the film industry in 1937, served with the AFPU working on ‘Desert Victory’, ‘Tunisian Victory’ and ‘Burma Victory’ with Roy Boulting.

After the war he went on to, work at Shepperton Studios as music and dubbing mixer on notable films including ‘Bridge on the River Kwai’ and ‘Laurence of Arabia’. From 1972 he was Head of Sound at Rank Film Laboratories until his retirement.

During his illustrious career he had many film credits as sound recordist and mixer, including ‘Mary Queen of Scots’ (Oscar nominated), ‘Anne of a Thousand Days’ (Oscar nominated), ‘The Italian Job’, ‘Girl on a Motorcycle’, ‘Far From the Madding Crowd’, ‘Half a Sixpence’, ‘The Quiller Memorandum’, ‘Doctor Strangelove’, ‘Lawrence of Arabia’, ‘The Guns of Navarone’ and ‘In Which We Serve’.

Gillie Potter joined the AFPU, already having started his career with the National Screen Service as a Title Artist, and was posted to Mountbatten’s South East Asia Command, where he stayed after the war ended to assist in setting up the Malaysian Government Film Unit. After a few years working in Malaysia he returned to the UK just in time for the start-up of ITV.

He was one of the world’s leading special effects animators and became known as the man who could ‘do the impossible’. His revolutionary work in British commercials advanced the use of specialist ‘in-camera’ effects. He elevated the boring ‘pack-shot’ to an art form and invented the device of having live action sequences taking place on a moving product pack. His work earned him more than 40 international awards including a Golden Lion at the Cannes Advertising Film Festival – and he was involved in the production of more than 2,000 advertisements. His special effects work can also be seen in feature films including ‘The Last Emperor’, ‘Superman: The Movie’ and ‘Jurassic Park’.

Harry Waxman started with International Pictures as a camera assistant and worked in a number of studios during the 1930s, including Ealing, Welwyn and Worton Hall.

During the war he served with the RAF Film Unit making his first feature, ‘Journey Together’, directed by John Boulting in 1945. His work on that film led to a contract with Two Cities Films after the war leading to him working at Denham Studios and becoming involved with the Boulting brothers as cameraman on ‘Fame Is the Spur’ and then as cinematographer on ‘Brighton Rock’ both in 1947.

Harry Waxman was a founder-member of the BSC (British Society of Cinematographers) and served as President from 1966-69 – and in 1959 he won an award from the British Society of Cinematographers for ‘Sapphire’. He is credited with more than 60 other films included ‘Swiss Family Robinson’, ‘The Day the Earth Caught Fire’, ‘Crooks in Cloisters’, ‘The Nanny’, ‘The Anniversary’, ‘The Wicker Man’.

The dedicated and outstanding work of the members of the AFPU and the RAFFPU is carried on by the photographers and cameramen of the Royal Logistics Corps, 77th Brigade who are the current British Armed Forces members working wherever the Army, Navy and RAF are deployed. Perhaps one day we’ll see one or two of their names credited in award-winning dramas or documentaries, like their predecessors!